You’ve undoubtedly seen it, and may aggravate you as you drive by it. The sight of a mature tree that has been cut well below the height it should be reaching. This tree, sadly, has been Topped. It is as unnatural as it seems, a huge trunk with a tiny sphere of leaves. This is, sadly, a very common practice–especially when done on trees beneath power lines. The priority in this practice is to clear the right-of-way of the utility lines. Utility companies are obliged to maintain a certain amount of clearance between high-voltage lines and tree limbs. If a branch were to come in contact with these conductors, or worse, fall during a storm or failure, the results could be catastrophic for the tree and residents.

Of course, this could be avoided well before this issue comes up by picking the proper species (TreePeople only plants trees suitable for growth below powerlines) but this is a lesson that must, ostensibly, be relearned by municipalities and landowners all over the world. What about those trees for whom utility lines are not a concern? Is topping a tree justifiable or even recommended?

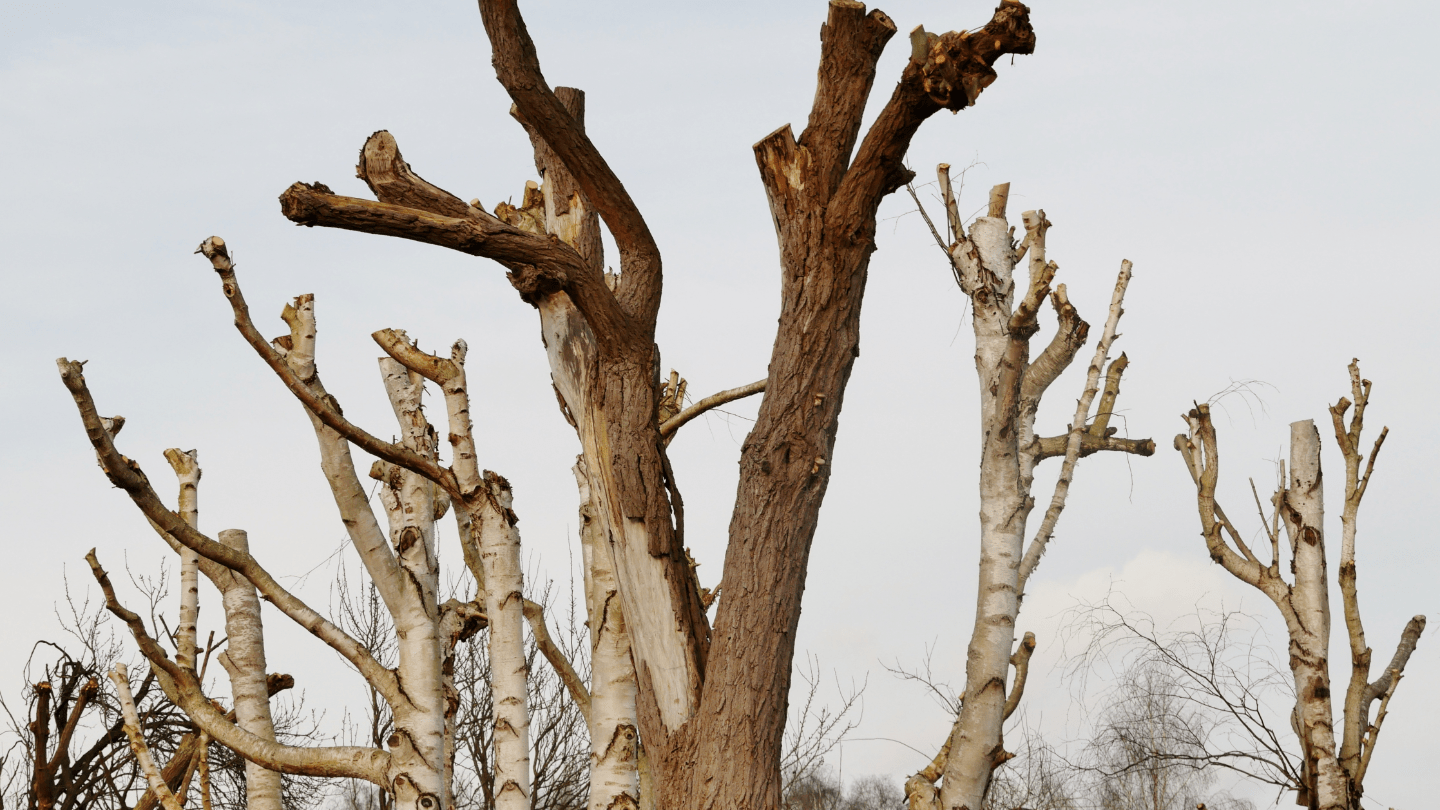

WHEN TOPPING IS UNAVOIDABLE

Believe it or not, there may be a few scenarios where topping is unavoidable. Certain trees, especially fast upright growing ones, that have the poor luck of being planted beneath utility lines may be fated for topping. Undoubtedly, those trees will have to be replaced with smaller ones eventually, but even the topped tree might provide some value.

Another possible scenario is when trees are damaged during extreme weather events. If they represent a real threat to nearby targets (people or property) and don’t have suitable lateral limbs that can be cut, the tree may need topping. This ideally would be followed by years of restorative pruning to help re-establish the natural form of the species.

Say your large tree isn’t an imminent hazard, nor is it destined to conflict with utility lines: is it still ok to top? The answer is a resounding NO. “But why? My neighbor topped their tree, and it’s pushing out all sorts of growth. Also, I just can’t afford to maintain such a large tree. I don’t want this thing to fall on me! My landscaper (who isn’t an arborist) told me it’s fine…”

The reality is that any person with a chainsaw can advertise themselves as a tree worker, and disinformation is abundant in the industry as it is with many others during this age of information. However, tree care professionals are unanimous in their disapproval of this practice.

Practices that appear similar but are distinct from topping:

- Pollarding: a common type of pruning that is common across the globe. It involves cutting a young or mature tree to a desirable height after the tree has developed appropriate radial distribution of its limbs. After some years, the tree develops a callused growth at the tip of the limbs called a knuckle or pollard-head. Many young shoots develop from this pollard-head, year after year, which are annually removed at the appropriate time. The important distinction is that only certain species are appropriate for this cosmetic practice, and the pollard heads must never be wounded when pruning off the annual shoots.

- Topiary, Espalier & Bonsai: less common pruning styles, but they involve a similar practice of limiting the size of trees/tree-like shrubs. These practices require patient long-term maintenance and careful planning and usually require species that can tolerate potentially stressful practices.

WHY IS TOPPING BAD FOR TREES

Trees are immobile and often resilient, and we can sometimes forget that they are organisms that can thrive or struggle, can be prolific, or can fall into decline. The issue of our safety should also align our practices with this reality: while trees are infrastructure, they are also living organisms that are vulnerable to injury, sickness, and death. When a tree is stressed or mortally injured, it is far more likely to fail. Here are some physiological responses of trees to topping:

- Starvation: Trees are autotrophs. They make their food through photosynthesis, turning water, sunlight, and carbon into food that powers all the various metabolic processes that continuously run inside the tree’s organs. The leaves and limbs are its primary way of powering these other vital processes by producing photosynthates. When we remove a tree’s leaves and limbs aggressively, we are causing an energy deficit in the tree. This means less energy to grow but, also, to compartmentalize wounds, to support healthy roots, and to fight off pathogens. Starving trees are far more likely to enter irreversible decline.

- Disease and decay: Trees have special internal barriers designed to wall off the spread of disease and decay. Topping trees completely circumvents these barriers, leaving the tree completely open and vulnerable to decay that may eventually kill it or cause the remaining limbs to fail without warning. Certain diseases may also take advantage of stressed trees to reproduce and spread to other nearby trees and plants. Harmful pest populations more often seek stressed trees to infest as they can’t respond to infestations with their natural defenses.

- Water Sprouts: One way trees often respond to topping is to use emergency stores of energy to push out as many emergency branches as quickly as possible. These are called water sprouts, and they are the way trees cope with starvation. However, these branches are anatomically much weaker than naturally occurring branches and often grow clustered with one another. As they continue to grow, their proximity to one another can cause breakage, further exacerbated by their weak attachment points, which can become hazardous if they grow large enough. Additionally, these water sprouts are dissimilar from natural branches in that they don’t feature many of the internal defenses to pests and diseases and are much more likely to become sickly or infested.

- Disfigurement: Many people think that the most beautiful trees are the healthiest trees. Topping a tree doesn’t just shorten its life span, it makes it unsightly. Trees can exhibit a variety of graceful and robust forms; topping eliminates the possibility of a tree achieving its maximum value as a specimen.

- Death: As mentioned previously, the many processes that keep a tree thriving for decades abruptly ends the moment it is topped. From then on, most trees will struggle even in the most ideal circumstances. It is rarely a single issue that falls a tree, but topping one will undermine its ability to endure even the most minor obstacles. It will often cause a tree to become a hazardous liability rather than an enduring asset for the urban ecosystem.